In this detailed Muscle and Motion article, you will learn about the structure and function of the knee joint, including bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons. The anatomy of the knee joint is complex and intricate, allowing for a wide range of motion. In this article, we will explore the anatomy of the knee, its functions, and how it plays an integral role in human movement and function.

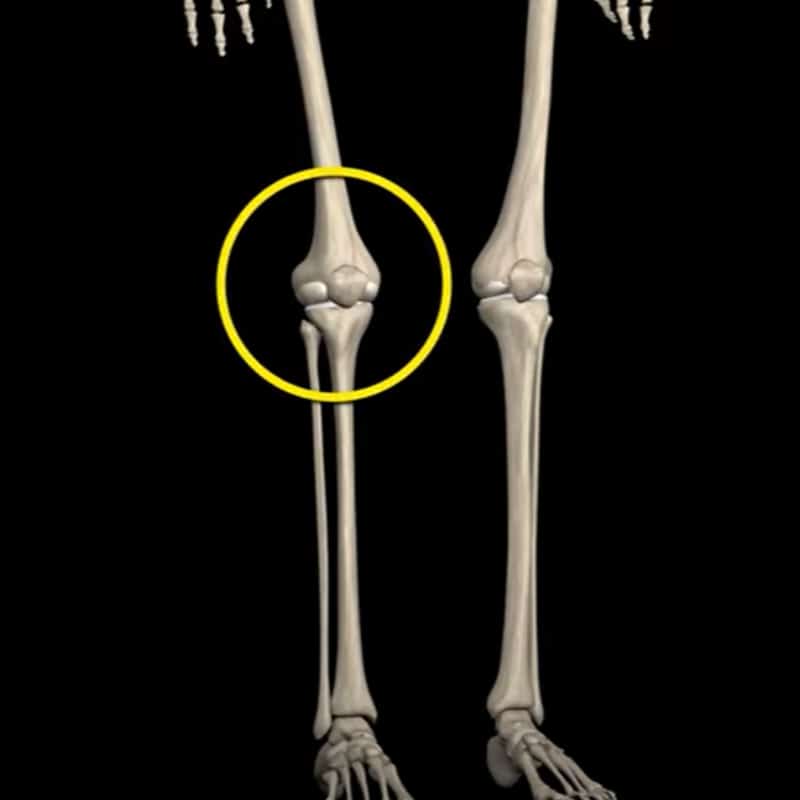

We will also discuss how the knee works in unison with the other leg components to provide an efficient and effective range of motion. The knee is a hinge synovial joint composed of four bones, ligaments, and muscles, all working together to provide stability and mobility.

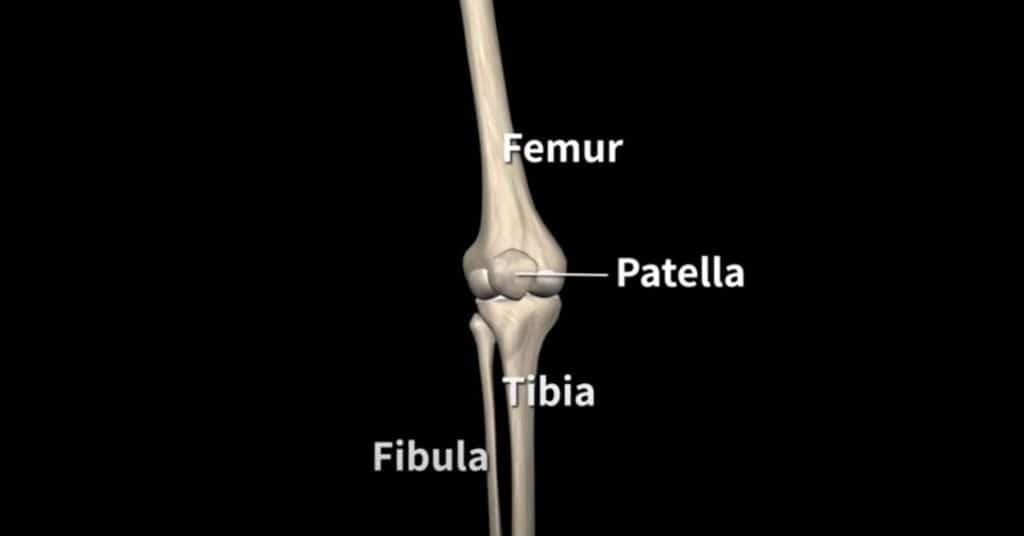

There are four bones that form the knee joint:

- The thigh bone (the femur)

- The shin bone (the tibia)

- The kneecap (the patella)

- The fibula

The knee joint is a synovial joint. Synovial joints are enclosed by a ligament capsule and contain a fluid called synovial fluid that lubricates the joint.

Both joints are covered with articular cartilage. This slippery substance allows the surfaces to slide against one another without damage to either surface.

The function of articular cartilage is to absorb shock and provide an extremely smooth surface to facilitate motion.

The anatomy of the knee joint

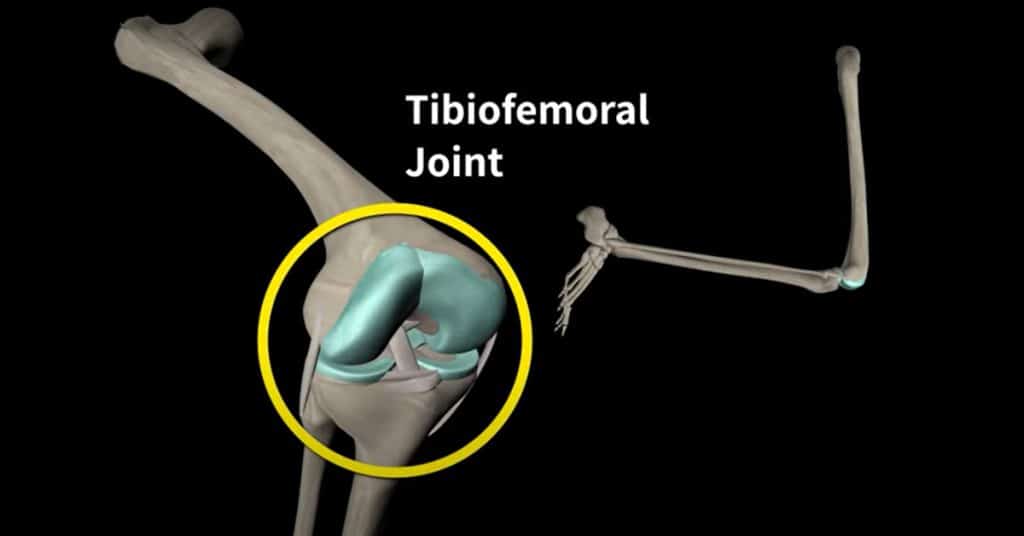

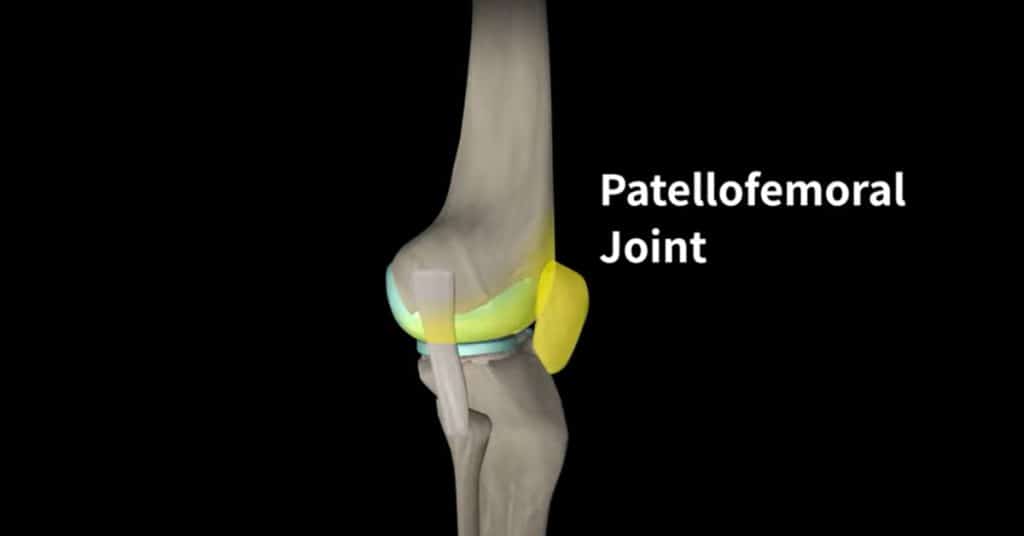

The knee is made up of 4 bones, but it is composed primarily of 2 joints.

- The tibiofemoral joint – the part of the knee between the end of the thigh bone (the femur) and the top of the shin bone (the tibia).

- The patellofemoral joint – located between the end of the femur and the patella.

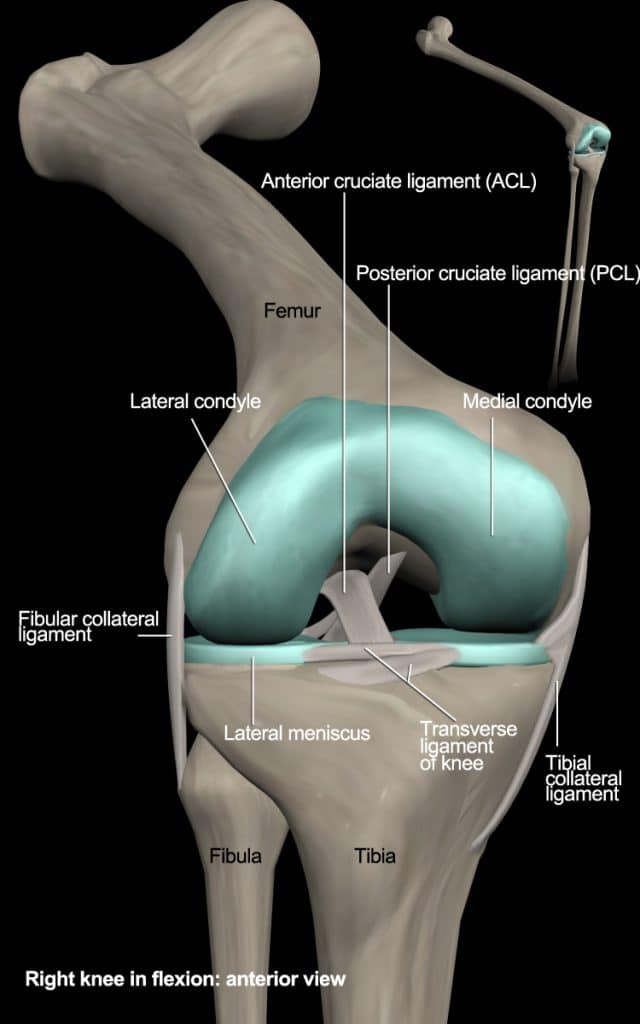

The anatomy of the knee ligaments

The knee is composed of numerous ligaments which provide additional stability and help protect it from excessive motion. Let’s take a look at the four most important ligaments:

1. Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

The Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) is located on the inner side of the knee. This ligament connects the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia), offering stability and strength to the knee joint. The MCL provides valgus stability to the knee joint, and it is the most commonly injured knee ligament.[1]

2. Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) is located on the outer side of the knee. This ligament connects the thigh bone (femur) to the fibula, offering stability and strength to the knee joint. The LCL prevents excessive inward angling (varus) and posterior-lateral rotation of the knee. Inside the knee joint are two other important ligaments that stretch between the femur and the tibia: the ACL and the PCL.

3. Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is located inside the knee joint in front of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL). This ligament keeps the tibia from sliding too far forward in relation to the femur. Depending on the knee angle, it prevents excessive varus/valgus stresses and tibial rotation.[2] The ACL also plays an important role in detecting changes in the direction of movement, the position of the knee joint, and changes in acceleration, speed, and tension.

4. Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

The Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) is located inside the knee, just behind the ACL. The PCL keeps the tibia from sliding too far backward in relation to the femur. This ligament resists excessive posterior translation of the shin bone (tibia) in relation to the thigh bone (femur). It also acts as a secondary knee stabilizer by preventing excessive rotation, specifically at a knee flexion range of 90° to 120°. [3] Together, the ACL and PCL control the back-and-forth motion of the knee.

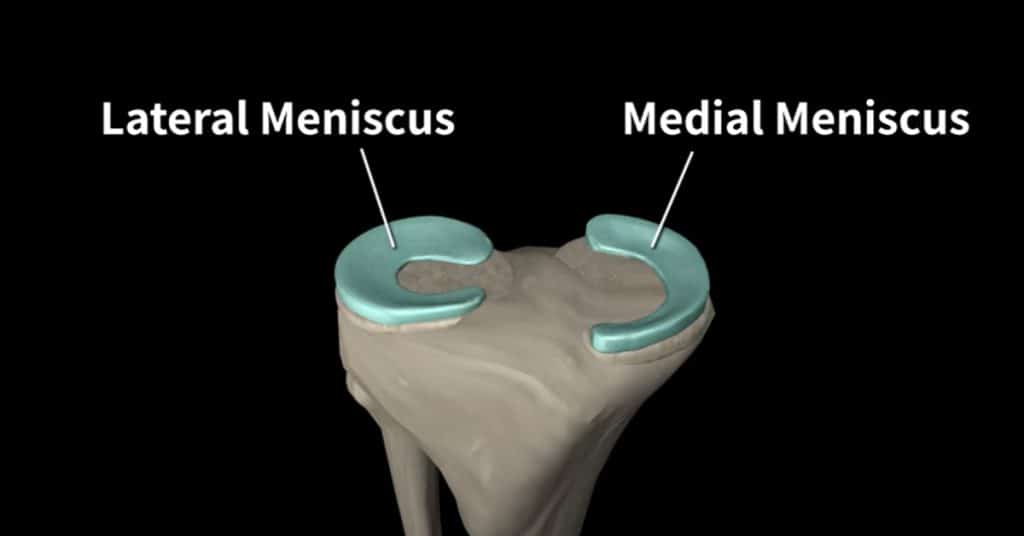

The anatomy of the knee meniscus

The menisci of the knee are two crescent-shaped pieces of cartilage that act like gaskets and cushion contact between the femoral and tibial condyles, helping to distribute the force of the body’s weight over a larger area and protect the joint cartilage. Additionally, the menisci help to stabilize the knee by acting like wedges, with their thicker outer edges helping to keep the round femur from rolling on the flat tibia. The meniscus and ligaments provide static stability, and muscles and tendons provide dynamic stability.

Knee joint movement

Before discussing the muscles around the knee, it is important to understand the range of motion the knee allows.

The primary motion of the knee joint occurs in the sagittal plane, allowing for flexion (bending) and extension (straightening) of the knee. In this case, the knee acts as a hinge joint, where the articular surfaces of the femur roll and glide over the tibial surface. During flexion and extension, the tibia and patella act as one structure in relation to the femur.

The knee joint also includes rotational movement between the femur and the tibia. This rotational movement is part of the “screw-home” mechanism, a key element of knee stability. It occurs at the end of knee extension, between full extension (0 degrees) and 20 degrees of knee flexion. However, the tibia does rotate internally during open chain movements (the swing phase) and externally during closed chain movements (the stance phase).

Muscles and tendons surrounding the knee

Many muscles surround the knee joint and move the knee joint back and forth. When the muscles contract, the tendons are pulled, and the bone is moved. This part of the article will discuss the muscles surrounding the knee joint.

Let’s begin with the knee extensor muscles.

The extensor muscles of the knee

The primary extensor muscles of the knee joint are the quadriceps femoris, assisted by the tensor fasciae latae.

-

Quadriceps femoris

The quadriceps femoris comprises four heads; three heads originate from the femur, and the fourth head, the rectus femoris, originates from the anterior superior iliac spine. The muscles that form the quadriceps femoris unite proximal to the knee and attach to the patella via the quadriceps tendon. In turn, the patella is attached to the tibial tuberosity by the patella ligament.

For more detailed information about the quadriceps femoris anatomy and function, check out this video:

-

Tensor fasciae latae

The tensor fasciae latae (TFL) is attached to the iliotibial band. The iliotibial band descends inferiorly and inserts into the lateral condyle of the tibia, also known as Gerdy’s tubercle.

For more detailed information about the tensor fasciae latae anatomy and function, check out this video:

We’ve reviewed the knee extensor muscles. Now let’s review the knee flexor muscles.

The flexor muscles of the knee

The primary knee flexor muscles are the hamstrings, assisted by the sartorius, the gracilis, the gastrocnemius, and the popliteus.

-

Hamstrings

The hamstrings muscle consists of three long separate muscles; these muscles originate from the ischial tuberosity and insert below the knee joint.

- The semimembranosus inserts into the posterior medial condyle of the tibia.

- The semitendinosus inserts into the medial surface of the proximal tibia.

- The biceps femoris has two heads: short and long.

Both heads insert into the fibula but differ in their origin point. While almost all the hamstring muscles originate from the ischial tuberosity, the only exception is the short head of the biceps femoris which originates from the posterior femur.

-

Sartorius

The sartorius originates from the pelvis and descends in an S-shape to below the knee, behind the medial head of the quadriceps. The sartorius and the gracilis, along with the semitendinosus, all insert into the anteromedial aspect of the tibia, also known as pes anserinus or “goose foot”.

-

Gracilis

The gracilis is a long, thin muscle located in the medial part of the thigh. It originates from the medial aspect of the ischiopubic ramus. It inserts into the pes anserinus along with the sartorius and semitendinosus.

-

Gastrocnemius

The gastrocnemius is a large superficial muscle located in the posterior leg. It has two heads: the medial head, and the lateral head

- The medial head originates from the medial epicondyles of the femur.

- The lateral head originates from the lateral epicondyles of the femur.

Both heads connect into the Achilles tendon and insert into the calcaneus.

-

Popliteus

The last knee flexor muscle is the popliteus. The popliteus muscle initiates knee flexion and unlocks the knee. It originates from the lateral femoral condyle and inserts into the posterior surface of the proximal tibia.

Dive deeper into our content – Download our Strength Training App Today.

Written by Uriah Turkel, Physical Therapist and Content Creator at Muscle and Motion.

Reference:

- Chen, L., Kim, P. D., Ahmad, C. S., & Levine, W. N. (2008). Medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee: current treatment concepts. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 1(2), 108–113.

- Petersen W, Zantop T. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament with regard to its two bundles. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007 Jan;454:35-47

- Papannagari R, et al. Function of posterior cruciate ligament bundles during in vivo knee flexion. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007 Sep;35(9):1507-12.