By: Ryan R. Fairall, PhD, CSCS, ACSM-EP, NASM-CPT, CES, PES

The Importance of Performing a Static Postural Assessment With Clients

Over the last decade or so, assessing clients’, patients’, and athletes’ static and dynamic posture has become a common practice during initial and follow-up health and fitness assessments. This has been a great step forward for the field of health and fitness and assisting practitioners (e.g., personal trainers, strength and conditioning coaches, athletic trainers, etc.) in spotting possible static postural deviations and/or movement compensations that may eventually lead to injury and/or performance decrements.

This Muscle and Motion article briefly describes how to assess the foot and ankle region during a static postural assessment to prevent the chain effects of foot overpronation. As well as how static deviations, such as foot overpronation, can lead to unwanted and potentially dangerous static postural deviations throughout the kinetic chain (i.e., knees, hips, pelvis, and lumbar spine) that may result in both acute and/or chronic musculoskeletal conditions.

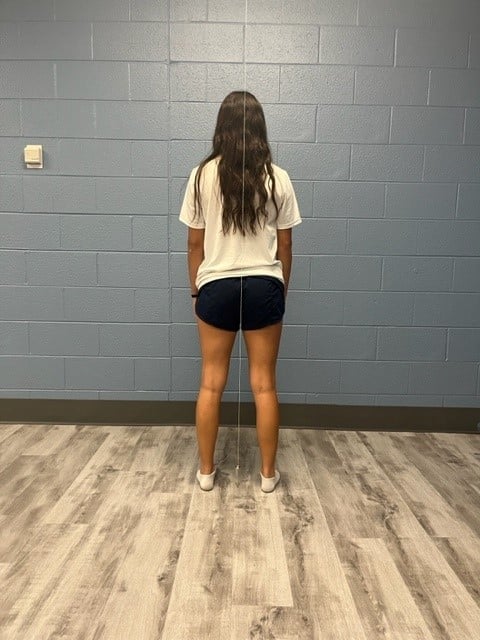

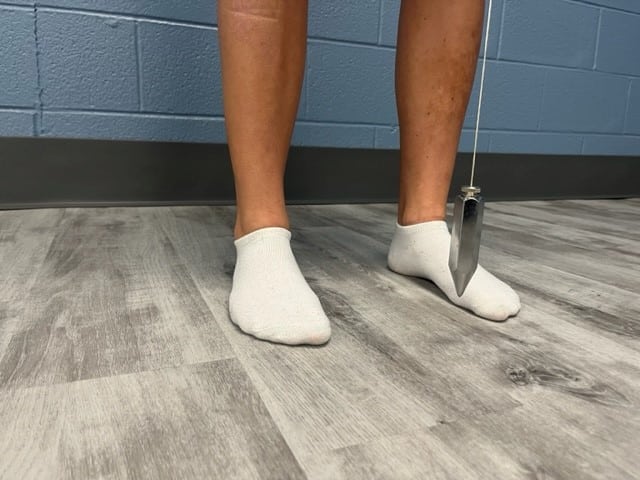

How to Assess Static Ankle and Foot Posture

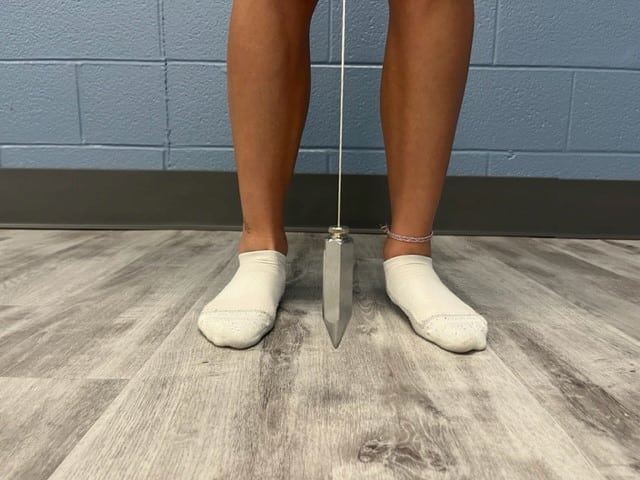

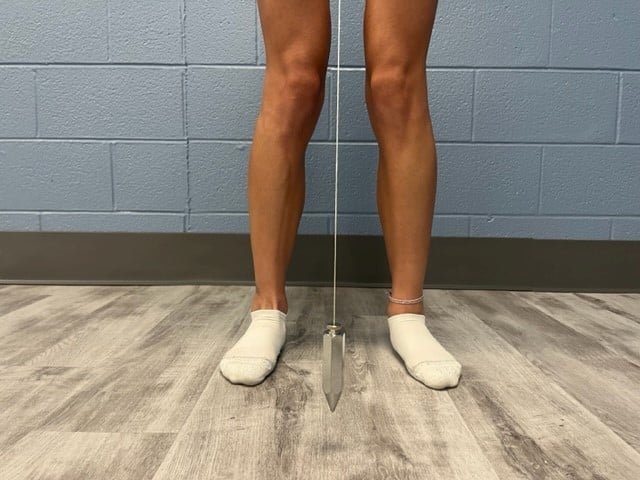

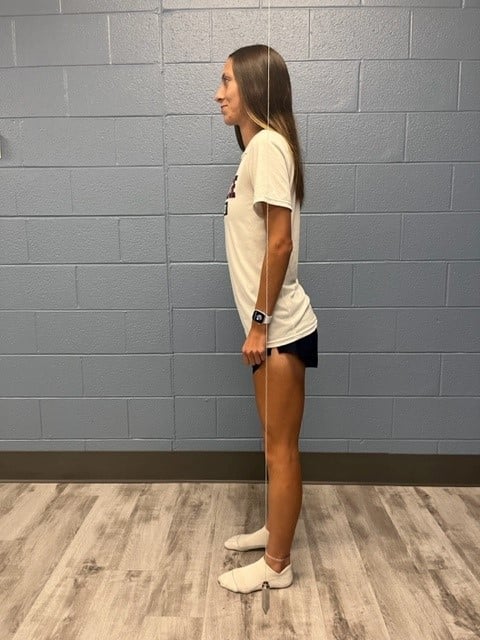

When assessing the foot and ankle region, the practitioner should assess the client primarily from the anterior view (Figure 1). Please note, assessing the client from the posterior view could assist the practitioner in confirming findings from the anterior view (Figure 2). The use of a plumb line as a point of reference could assist with assessing other regions of the body and identifying deviations and asymmetries. If a plumb line is unavailable, a posture grid or even lining the client up to a vertical line on the wall behind them can also work.

A plumb line is a cord or string with a plumb bob suspended from the ceiling to create an absolute vertical line. When using the plumb line from the anterior and posterior views, the plumb line should be aligned with the bob suspended midway between the feet and should divide the client equally into left and right halves.[1] The client should be asked to step up to the plumb line (if used) and to stand naturally. Some practitioners have used techniques such as having the client “shake out their body” or perform a few miniature squats to help the client feel more comfortable and relaxed in an attempt to have the client exhibit a more natural, everyday posture.

Figure 1

Figure 2

What is an “Ideal” Foot and Ankle Static Posture?

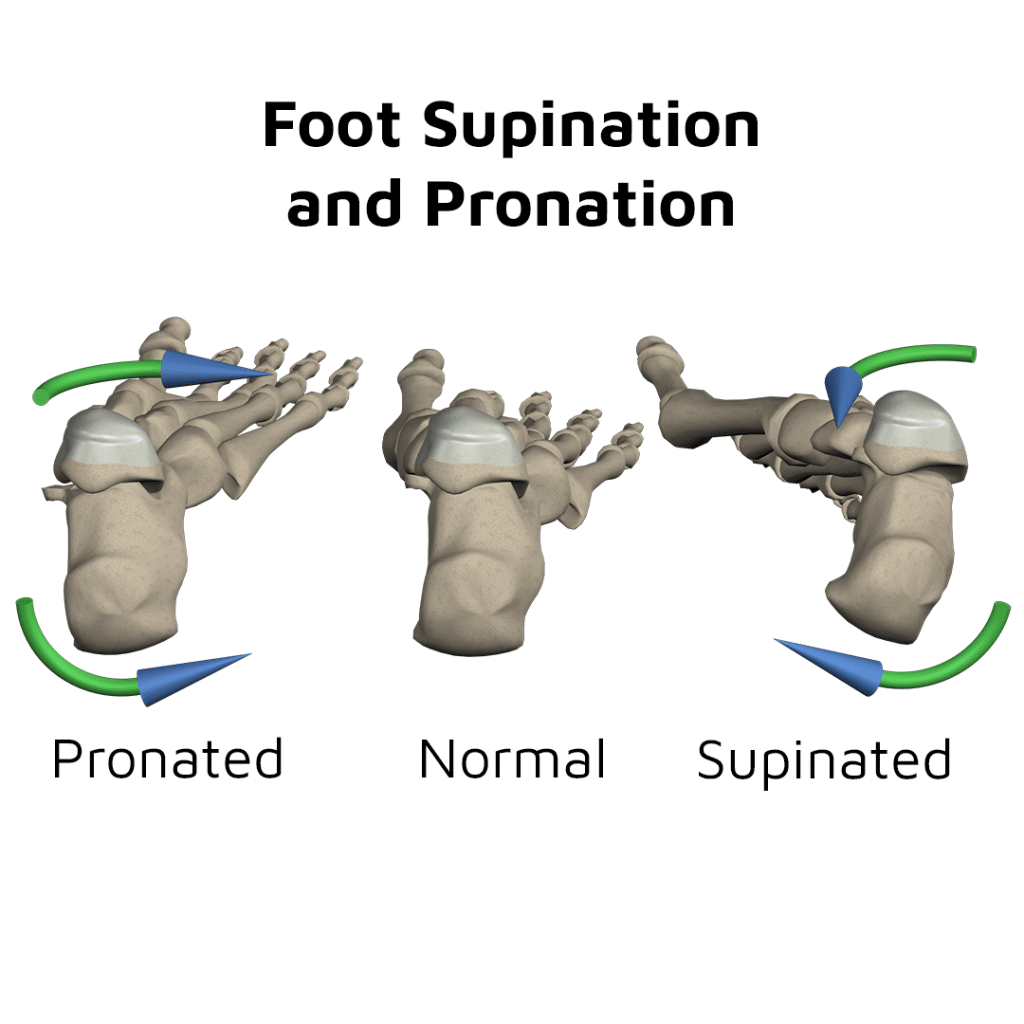

When assessing the foot and ankle region from the anterior view, the client should be unshod (i.e., no footwear, but socks are acceptable), their feet should be straight or slightly pointed outward, the foot should exhibit a neutral medial longitudinal arch (i.e., not too high of an arch and not too low or flattening of the arch), and the ankle should be in a neutral position (i.e., not plantar or dorsiflexed) (Figure 3). It is important to mention that foot pronation during movements like gait, squatting, and lunging is completely natural.

Figure 3

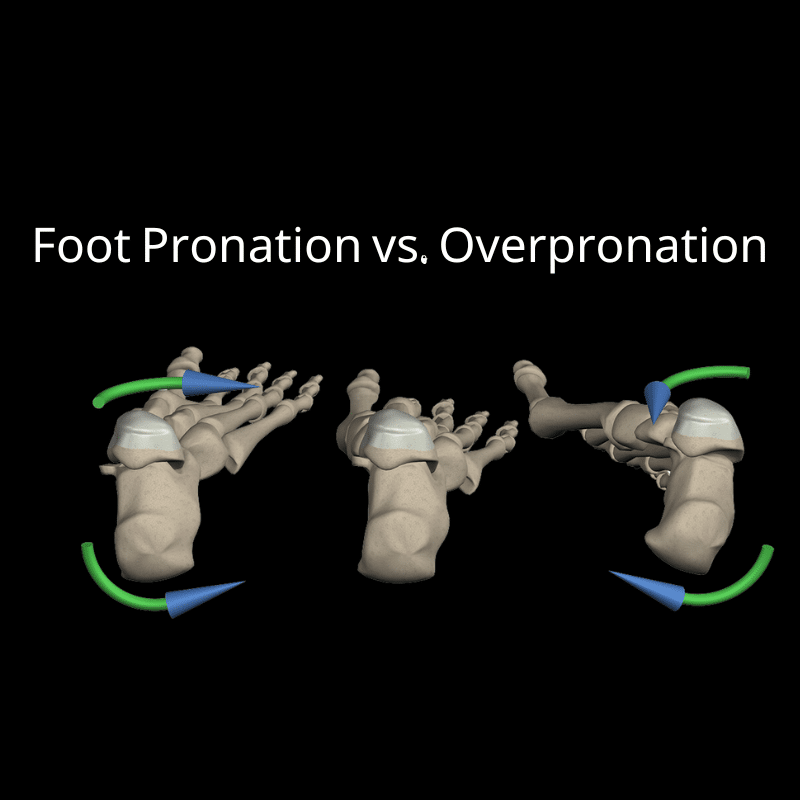

Foot Pronation vs. Overpronation

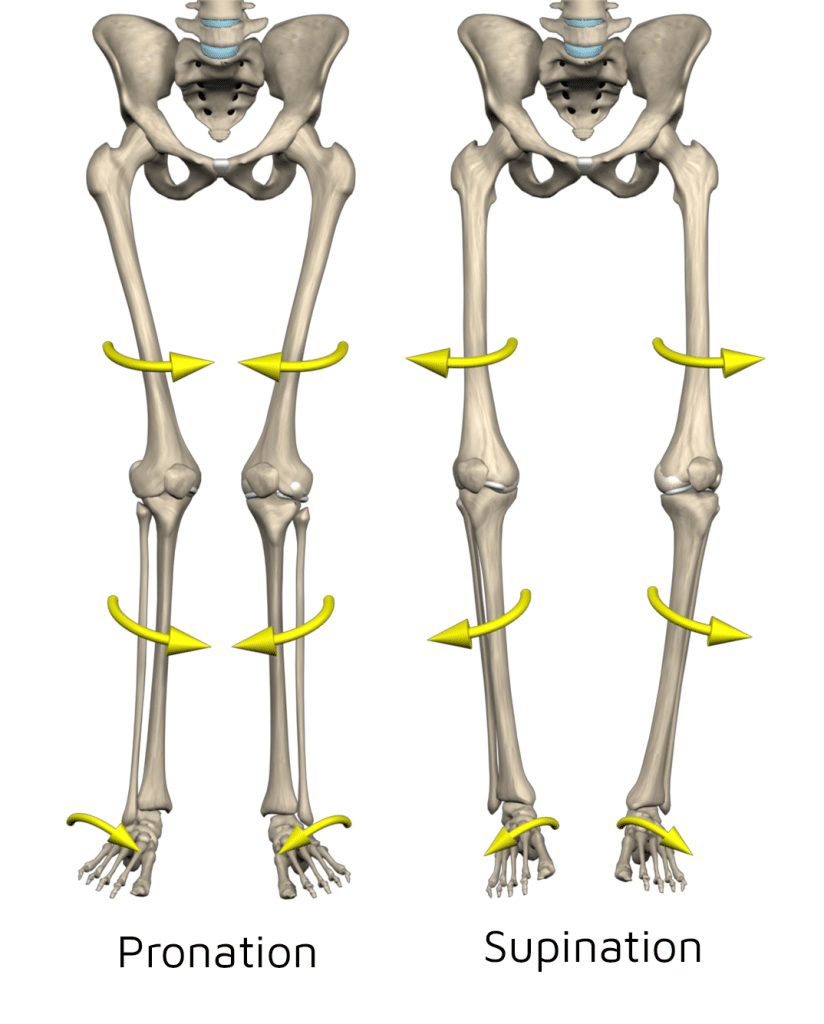

Pronation is a tri-planar static position or movement resulting from a combination of ankle

dorsiflexion, subtalar eversion, and forefoot abduction (i.e., toes slightly turning out).[2] However, when the foot has too much of these joint actions, either statically or dynamically, it is known as foot overpronation (Figure 4). Foot overpronation has been coined “pronation distortion syndrome” and “pes planus distortion syndrome”, which is commonly referred to as “flatfeet” due to the decrease or flattening of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot.[3]

Figure 4

Be Patient When Assessing Static Posture

Deviations from a normal foot and ankle static posture from an anterior and posterior view could be subjectively described as slight, moderate, or marked.[4] However, if the practitioner feels conflicted as to if the foot overpronation is slight or even moderate, the practitioner need not panic. Signs of foot overpronation will become much more apparent during further assessment via movement screens like the overhead squat assessment, single-leg squat assessment, and gait. If the practitioner witnesses either unilateral or bilateral overpronation, they should note this in their health and fitness assessment documentation and keep this information in mind as they continue their static and dynamic postural assessments.

Their Effects Foot Overpronation on the Kinetic Chain: Knees and Hips

Because the human body is comprised of an interlinked skeletal system chain, as well as subsystems consisting of muscles, tendons, and fascia, a postural deviation at one region of the body can in some cases have an effect on the region above and/or below that region. This has been referred to as the “regional interdependence model” or “RI”. [5] For example, foot overpronation can lead to compensations upward throughout the kinetic chain. With foot overpronation, it is common for the client’s knees to move inward within the frontal plane, also referred to as knee or genu valgus or valgum, also known as “knock knees” (Figure 5). Moving up from the knee joints, the client’s hips will commonly adduct and internally rotate creating an excessive inward angle of the femur from the hip joint to the knee joint. Individuals, specifically women, naturally have an inward angle of the femur, also known as the quadriceps or Q-angle, due to a naturally wider pelvis when compared to males. However, foot overpronation can lead to an even greater angle, increasing the risk of both acute (e.g., ACL tears, MCL tears, and meniscus injuries) and chronic (e.g., patellar tendonopathy, patellofemoral pain syndrome, chondromalacia, and osteoarthritis) knee injuries. [6]

Figure 5

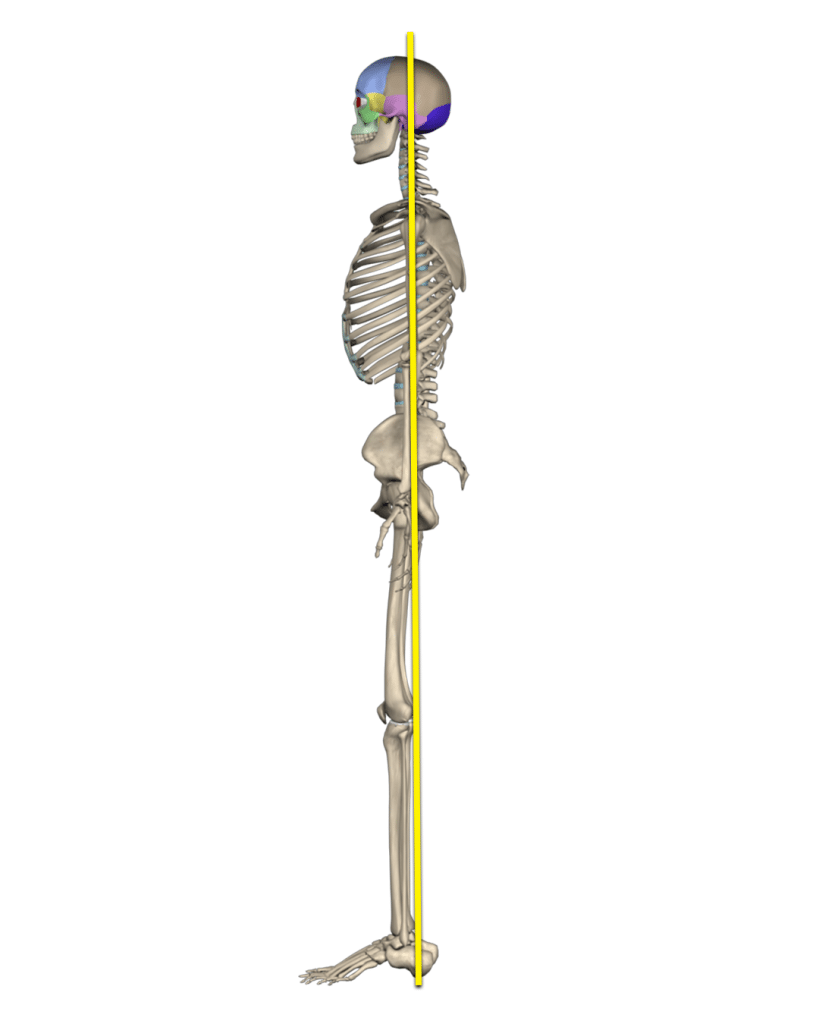

Their Effects Foot Overpronation on the Kinetic Chain: Lumbo-Pelvic Hip Complex

In addition to knee valgus, hip adduction, and hip internal rotation, clients with foot overpronation may exhibit slightly flexed hips, combined with an excessive anterior pelvic tilt and excessive lordosis of the lumbar spine when assessing the client’s static posture from a lateral view (Figure 6). Although it is common for asymptomatic individuals to possess a slight anterior pelvic tilt and a natural lordosis of the lumbar spine, an excessive pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis, also known as “lower crossed syndrome” or “pelvic crossed syndrome”, may lead to multiple musculoskeletal conditions within those regions, including multiple low back pain syndromes.[7] This is once again an example of the concept of the regional interdependence model with something believed to be as simple as foot overpronation leading to a possible debilitating condition such as chronic nonspecific low back pain.[8]

Figure 6

A Static Posture Assessment is Just the Beginning

Although assessing the static posture of the foot and ankle region is just the beginning of a comprehensive assessment of the human body both statically and dynamically, it is a key element to the static postural assessment. Therefore, if practitioners do not currently assess their clients’ static and dynamic postures, it would benefit both the practitioner and their clients by incorporating static and dynamic postural assessments into their health and fitness assessments. This will assist the practitioner in developing an individualized exercise program for their client in an attempt to decrease the risk of injury and improve performance.

At Muscle and Motion, we believe that good posture is essential for your long-term health and well-being. Our Posture App can help you improve your posture and reduce pain. Sign up for free today!

References:

- Cameron, M. H. & Monroe, L. J. (2007). Physical rehabilitation: Evidence-based examination, evaluation, and intervention. Elsevier.

- Floyd, R. T. (2024). Manual of structural kinesiology (22nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

- National Academy of Sports Medicine (2022). Static assessment. In R. Fahmy (Ed.), NASM essentials of corrective exercise training (pp. 184-210). (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Kendall, F. P., McCreary, E. K., Provance, P. G., Rodgers, M. M., & Romani, W. A. (2005). Muscles: Testing and function with posture and pain (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Sueki, D. G., Cleland, J. A., &Wainner, R. S. (2013). A regional interdependence model of musculoskeletal dysfunction: Research, mechanisms, and clinical implications. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 21(2), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1179/2042618612Y.0000000027

- National Academy of Sports Medicine (2022). Corrective strategies for the knee. In R. Fahmy (Ed.), NASM essentials of corrective exercise training (pp. 320-349). (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Key, J. (2010). The pelvic crossed syndromes: A reflection of imbalanced function in the myofascial envelope; A further exploration of Janda’s work. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 14(3), 299–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.01.008

- O’Leary, C. B., Cahill, C. R., Robinson, A. W., Barnes, M. J., & Hong, J. (2013). A systematic review: the effects of podiatrical deviations on nonspecific chronic low back pain. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 26(2), 117–23. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-130367