Shoulder pain during overhead movements can be frustrating and limit one’s ability to perform daily activities. However, there’s good news for those looking to better understand and manage this condition! In this detailed Muscle and Motion article, we’ll explore how our understanding of shoulder impingement syndrome has evolved, explore the latest research, and provide practical advice for managing and preventing shoulder pain.

The origins: Neer’s theory of shoulder impingement syndrome

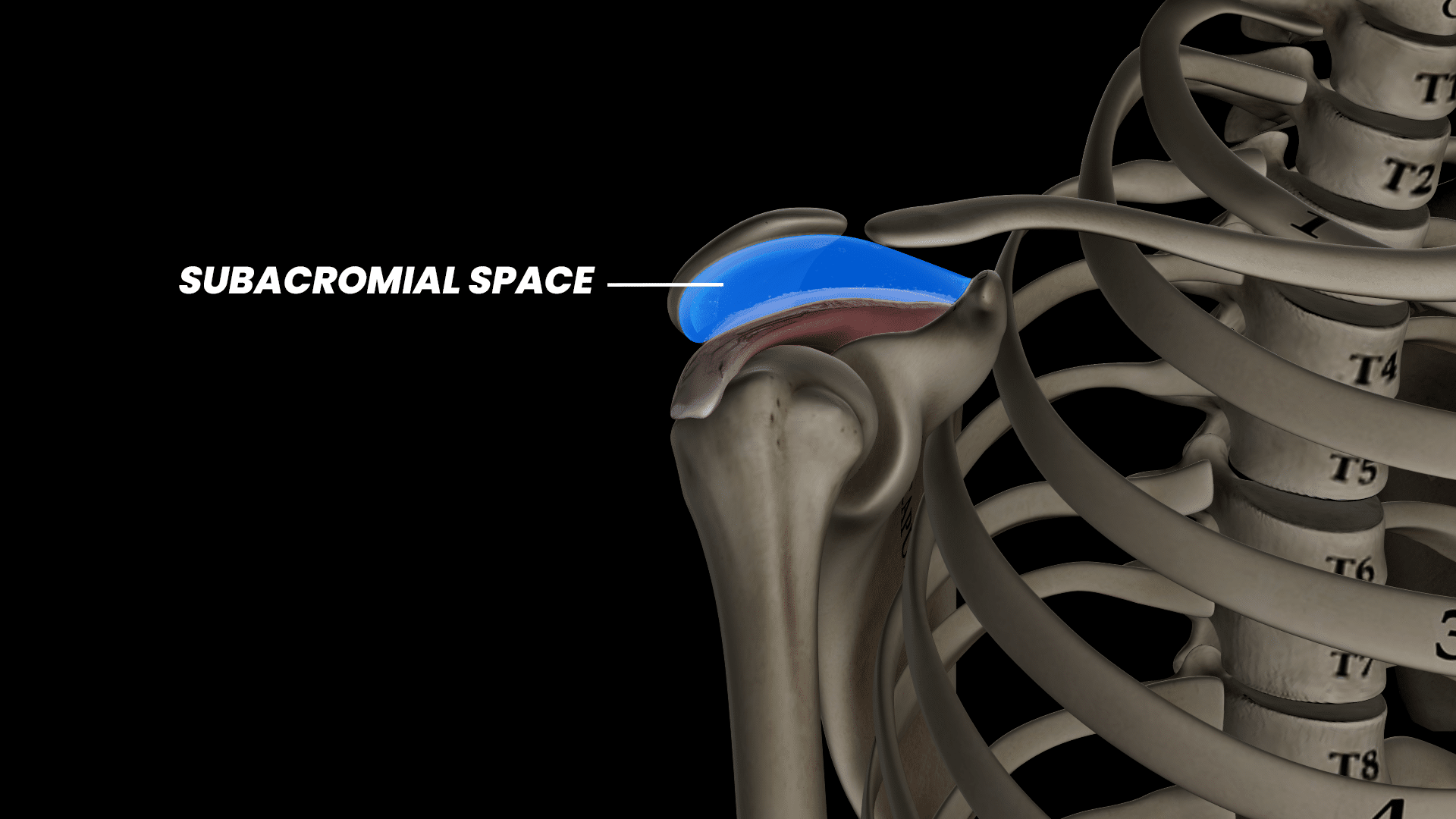

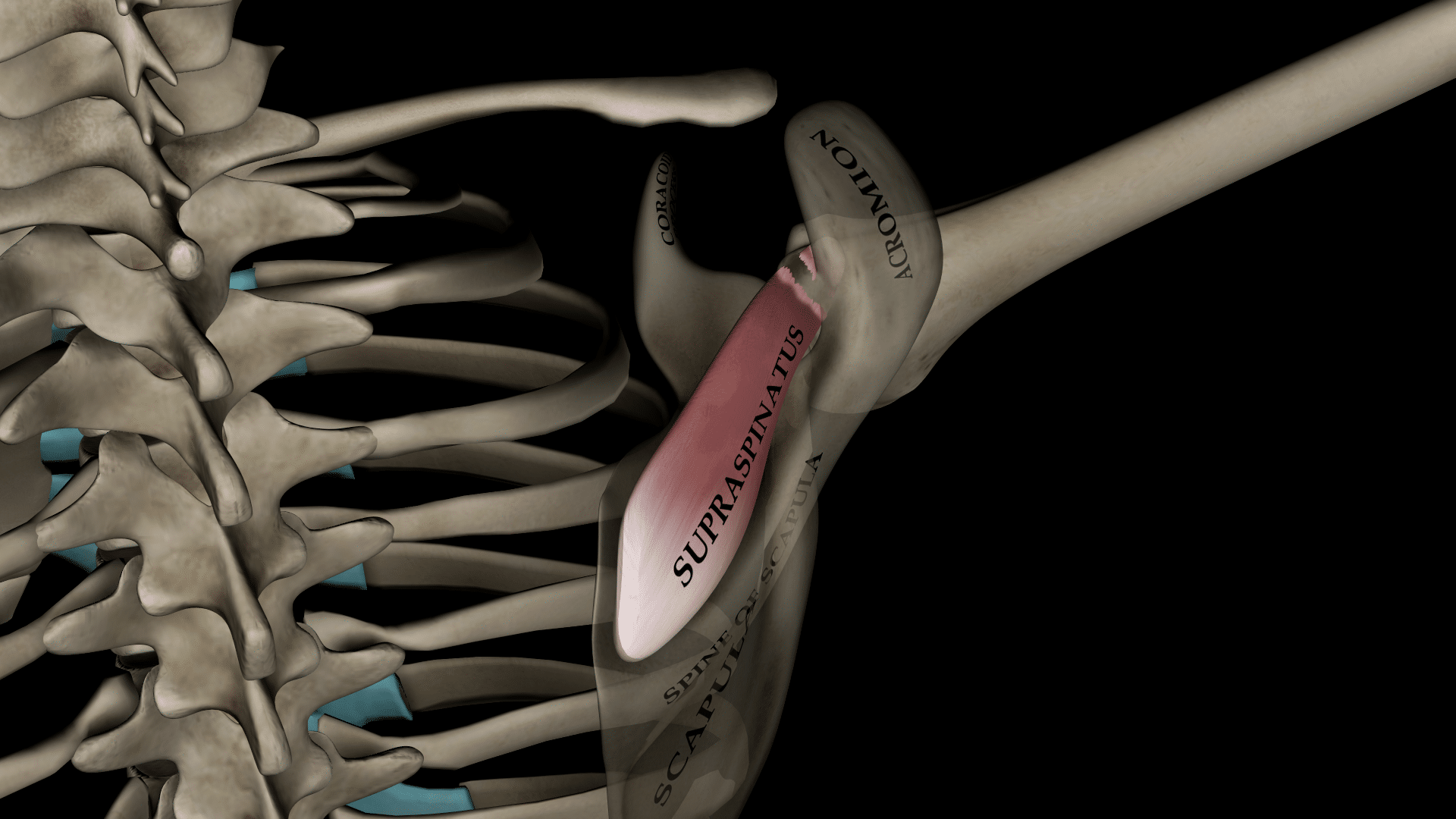

In 1972, Charles Neer introduced shoulder impingement syndrome, which he attributed to irritation of the supraspinatus tendon caused by the acromion located directly above it. According to Neer, a curved acromion reduces the space between the arm bone (humerus) and the shoulder blade, particularly during arm elevation. This subacromial space narrowing was believed to cause the acromion to “pinch” the supraspinatus tendon, resulting in tendon damage and shoulder pain.

To address this issue, Neer suggested a surgical intervention known as arthroscopic subacromial decompression, where part of the acromion is removed to relieve pressure on the underlying structures and prevent pinching.

Challenging the status quo: Recent findings

While Neer’s work influenced early treatment approaches, research has increasingly questioned several core aspects of his theory. Let’s explore what recent studies reveal:

1. Narrowed subacromial space

Contrary to Neer’s hypothesis, a meta-analysis by Park et al. (2016) found no difference in subacromial space size between individuals with and without shoulder impingement. Additionally, the study noted no correlation between the size of the joint space and pain or dysfunction. Interestingly, patients diagnosed with shoulder impingement often reported reduced pain over time without changing the joint space size. [1]

2. Location of rotator cuff tears

Neer’s theory attributed supraspinatus tendon tears to friction with the acromion. However, research by Payne et al. (1997) revealed that 91% of partial rotator cuff tears occur in the lower part of the tendon rather than the upper part, which would be expected if the acromion were responsible. [2]

3. Acromion shape and rotator cuff pathology

According to Neer, a curved or downward-sloping acromion was thought to increase the likelihood of supraspinatus tendon tears by reducing the subacromial space and creating mechanical friction during arm elevation. However, a study by Gill et al. (2002) investigated this relationship and found no significant correlation between the morphological structure of the acromion and the occurrence of rotator cuff tears.[3]

4. Effectiveness of surgery

A study by Beard et al. (2018) assessed the outcomes of three groups: one that underwent arthroscopic subacromial decompression surgery, another that received diagnostic surgery with no structural changes, and a control group with no surgical intervention. While the surgery successfully addressed the anatomical narrowing described by Neer six months post-surgery, the two surgical groups showed only minor improvements compared to the control group. These differences were not clinically significant, leading to re-evaluating the procedure’s effectiveness. As a result, arthroscopic subacromial decompression surgery, while initially believed to address the anatomical narrowing described by Neer, has been shown to provide minimal clinical benefits. This conclusion has led to its rare use in current practice, as the procedure’s invasiveness is not justified due to its limited effectiveness. [4]

The bigger picture: Multifactorial causes of shoulder pain

Emerging evidence suggests that shoulder pain cannot be attributed solely to mechanical factors like narrowed subacromial space or acromion shape. Instead, it involves a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Biological risk factors include age-related degenerative changes and rotator cuff tendinopathy. Psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and fear-avoidance behaviors can exacerbate the perception of pain. Social elements, including occupational demands and reduced physical activity, may further contribute. These elements vary among individuals and often interact with one another, making shoulder pain a multifaceted condition.

Practical advice for shoulder pain management

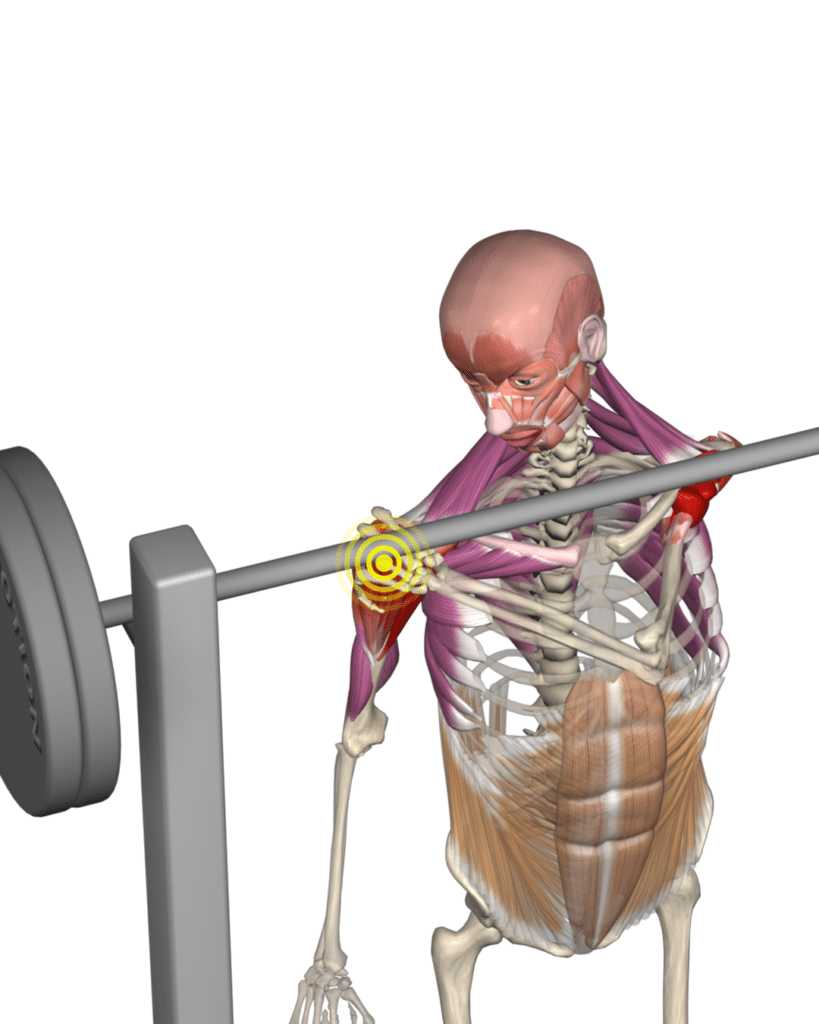

If you experience shoulder pain during overhead movements, consider these guidelines:

- Strengthen your shoulder muscles with controlled exercises that keep arm abduction below 90° of flexion, where the shoulder muscles function more optimally against the load.

- Identify shoulder exercises that do not provoke pain, such as isometric holds, external rotations with a resistance band, or scapular retraction exercises. Additionally, try elevating your arm in different shoulder positions, such as external or internal rotation, and experiment with arm abduction in the scapular plane (approximately 30° forward from the frontal plane) to identify pain-free angles and movements. Gradually increase the intensity and range of motion as tolerated, ensuring the muscles adapt without exacerbating discomfort.

- Focus on a comprehensive approach that addresses physical, potential psychological, and lifestyle factors contributing to pain. For example, metabolic issues such as obesity or diabetes can increase inflammation and serve as risk factors for non-traumatic shoulder pain. Addressing these through healthy eating and regular physical activity may help reduce discomfort and improve shoulder function.

To learn more about managing shoulder pain, check out our blog: Managing Rotator Cuff-Related Shoulder Pain.

At Muscle and Motion, we strive to provide you with the latest evidence-based information, empowering you to make informed decisions. By understanding the evolving perspectives on shoulder impingement syndrome, fitness professionals and athletes can adopt more effective, individualized strategies for managing and preventing shoulder pain.

Have you ever wondered what makes our anatomical animations so accurate and engaging? Click here to learn about our Quality Commitment and the experts behind our content.

At Muscle and Motion, we believe that knowledge is power, and understanding the ‘why’ behind any exercise is essential for your long-term success.

Let the Strength Training App help you achieve your goals! Sign up for free.

References

- Park, S. M., Choi, S. A., Jeong, H. J., Kim, M. J., & Kim, K. (2020). Effectiveness of exercise in reducing pain and disability associated with shoulder impingement syndrome: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8812.

- Payne, L. Z., Deng, X. H., & Craig, E. V. (1997). The prevalence of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 6(6), 517-523.

- Gill, T. J., McIrvin, E., Kocher, M. S., Homa, K., & Hawkins, R. J. (2002). The relationship of the acromion shape to rotator cuff tears. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(6), 789-794.

- Beard, D. J., Rees, J. L., Cook, J. A., Rombach, I., Cooper, C., & Merritt, N. (2018). Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): A multicenter, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomized surgical trial. The Lancet, 391(10118), 329-338.